When the first opportunity for electric speech across the Atlantic Ocean was realized with the 1858 transatlantic telegraph cable, the United States erupted into celebration. Parades wended their way through east coast cities, national figures gave grand speeches about instantaneous global unity, and fireworks lit up the sky. Artists produced memorabilia—from lithographs to coins—to commemorate the moment the U.S. could speak with Europe faster than a person could travel.

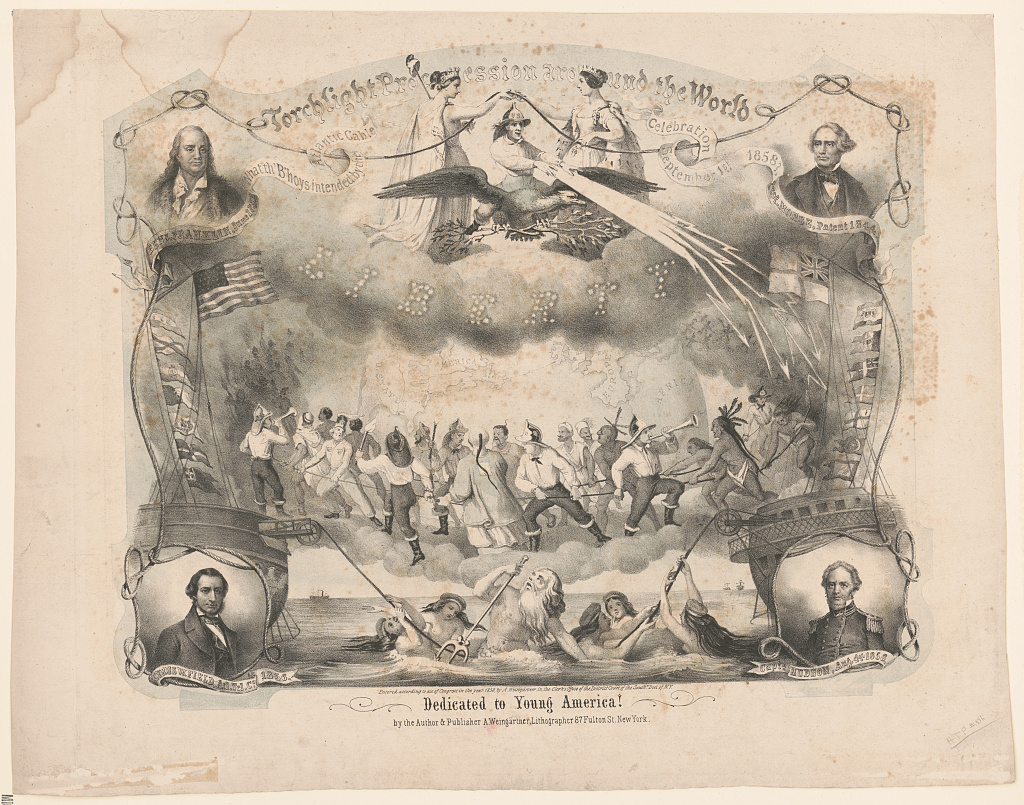

Indeed, the Atlantic Telegraph Cable of 1858 brought new forms of transnationalism into being, sutured the United States into a cabled network with Europe, and signaled the real possibility of electric global communication. Adam Weingärtner’s lithograph celebrating the event foregrounds a sense of international participation in the wiring of the Atlantic. And yet, for all the hailing of the grandeur of this global event, the lithograph (echoing American public discourse more broadly) rendered it surprisingly local. The celebration of the cable became a celebration of American vision, ingenuity, and gumption. A cult of heroism rewrote a complicated history of international scientific exchange into a singular myth of great U.S. inventors: Cyrus Hamlin, Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Morse. Here, these American heroes frame a representation of global cooperation. A place of transcendence is occupied by a NYC firefighter directing electricity toward the British ship. And the racialized images of global participation speak less to internationalism per se and more to the parochialism of American ideas about other inhabitants of the world.

“Popular enthusiasm” so marked public investment in these impossible imaginaries that one wry journalist named this period “the Great Fizzle,” which “developed Americans as the most enthusiastic believers in fables…in the world.” Indeed, U.S. celebrations of the power of Atlantic telegraphy to unify the world defied the conflicting reality of regular technological malfunction, the transnational fractures of colonial and anticolonial conflict, and the looming American Civil War, not to mention the fact that the cable actually connected the British colonies of Ireland and Canada.

American enthusiasm for the myth of electrically empowered global unity emerged from equally enthusiastic activity to obscure other forms of global relationship. Public discourse hailed connection; public practice entailed deep disconnections. There were, in fact, two telegraphs that crossed the sea that year. The Atlantic Telegraph Cable and a ship, the Telegraph, flying a U.S. flag and taking 654 enslaved Africans from West Central Africa to Sagua, Cuba. There is no mention of the slave trade in the overjoyed descriptions of global unity apparently presaged by transoceanic telegraphy. The American nationalism built around new networks was also built around a determined silence about the ways those networks fractured and excluded. To gloss Paul Gilroy, techno-nationalism has thrived on the fiction of “immutable differences between the histories of white and black.” The Atlantic Ocean was and remains a space of many exchanges—human, intellectual, commercial, electrical (now fiberoptic)—and our sense of networks must account for they way they are all twisted together under that salty water.