Netflix’s Teen Faith-Based Musical A Week Away Is A World Away from Our Pandemic and Hypermediated Society. It’s Also a Savvy Marketing Move.

On the Thursday just before Easter Sunday, Netflix pushed a cell phone notification to me with the subject heading, “Sarah, what are people watching in your area?” Netflix’s marketers were making strategic use of extensive marketing research data demonstrating that people are more likely to vote for candidates they think their neighbors are voting for, more likely to watch programs they think friends and co-workers watch, and more likely to consume the goods, services, and food they think people in their area use. My curiosity was piqued to see that an evangelical camp teen musical called A Week Away was the top streamed Netflix movie in my area. I live in a historic Catholic neighborhood of Chicago’s North Shore, which is alternatively referred to as the “Catholic Canyon” and the “Vatican Valley,” so the Netflix alert made me wonder why a movie about evangelical kids “getting saved” at church youth camp was so popular with my neighbors.

Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dpLaoYw8xug

Soon after this alert, I learned that A Week Away (directed by Roman White) holds special interest for North Shore Netflix viewers because our own local boy, adorable Kevin Quinn, raised in Wilmette, IL and a graduate of New Trier High School, stars in the film. Kevin has been acting since he was a little boy and got his start in our community theatre group, which happens to be located a few doors down from the Home Alone house, the stomping ground of another famous “Kevin.” In fact, one can hardly walk around the North Shore without stumbling upon a shooting location or tie-in to a John Hughes’s film. The very title The Breakfast Club comes from the colloquial term teens have for Saturday detention at New Trier, where Kevin Quinn appeared on stage before making it in Hollywood. (John Hughes films and references repeatedly make cameos in A Week a Way, so this connection will pop up again later.) Local boy hitting it big seemed reason enough for North Shore residents to be hunkered down watching a film that, as a number of viewers posting on social media have observed, looks a lot like what would happen if High School Musical had a baby with Camp Rock and then they sent that child as a teen to evangelical youth summer camp.

After watching A Week Away, I began reading through fan comments on social media, making my way through more than 1500 YouTube comments posted among those who had racked up 1.3 million-plus views for the official trailer. As a religion and media scholar (and sucked into a social media vortex), I was then compelled to read all the fan comments for Netflix’s posted official clips of the film. This, in turn, led me to read through all the comments for the posted soundtrack. In the course of reviewing all this data, something much more interesting emerged, inflected by the reception of this film in the Covid pandemic era. Close to a quarter of the comments in various comment sections were either written in Portuguese, or in English but posted by fans self-identified from Brazil, one of the hardest-hit Covid countries. The praise expressed for this “marvelous and perfect” film in these comments is exuberant, as are the urgent entreaties for Netflix to please provide film subtitles in Portuguese.

Considering the subject matter is evangelical church camp, there are also a surprising number of comments posted from ardent fans in India, another country devastated by Covid infections. I was unable to track down the name of the actress who does the Hindi voiceover for Bailee Madison’s lead role, but she does a great job, and musical love stories are indeed a popular film genre in India. Even so, the breadth of cultural appeal for a streaming-service-based U.S. evangelical teen film did make me wonder if other factors in our pandemic times are contributing to this phenomenon.

As I read through pages of comments from all over the world, it did not take long to click that the appeal of this film clearly extends far beyond a North Shore New Trier Kevin Quinn fanbase. During its Easter week debut, A Week Away ranked the 8th most popular Netflix title in the U.S., #3 in Brazil, #4 in India, #4 in Spain, and #6 in Germany and the Netherlands.

Reviewing the film for PopSugar, Kelsie Gibson’s tone is certainly less reverential than many of the effusive global fan postings, and yet she confesses, “Netflix’s New Musical A Week Away Is Super Cheesy, And I Need a Sequel Right Away.” Gibson is not alone. A whole thematic of commentary emerges of viewers who, in various ways, both declare the movie to be “cheesy” and then gush about how they love it anyway, or even specifically tout the cheese factor as a major selling point. Posters to the YouTube trailer and clips report watching the film ten times in a week, sometimes 5 times in one day, and identify themselves as “legit obsessed.” One poster claims to have listened to the film’s soundtrack 100 times. Another viewer confesses to watching the trailer over and over “just to feel something.”

Beyond simply the High School Musical appeal, which granted, counts for a lot, let’s explore 6 reasons why A Week Away might feel like a welcome antidote for pandemic-weary viewers around the globe, even those who might normally not gravitate to Christian-themed media. In examining the attraction of this film for our cultural moment, what also becomes clear is that this has been a savvy marketing move for Netflix. But first, to set the stage, here’s a quick synopsis of the film’s highly predictable plot. But hey, in the middle of a pandemic, predictable is good.

Will Hawkins (Kevin Quinn) is a troubled white teen who has bounced around foster homes since his parents were killed in a car crash, leaving him orphaned. Most recently, he “borrowed” a police car for a joy ride, got arrested, and is about to be shipped off to do time in “juvie.” He is informed he has one last chance. An African American family is willing to foster Will for the summer where they will bring him to the summer camp that employs the mother, Kristen (Sherri Shepherd), and where Kristen’s son George (Jahbril Cook) attends. After accepting this highly implausible deal of trading summer camp for “juvie,” Will, who rejected the idea of religion and God after his parents’ tragic death, is non-plussed by the revelation that he will be attending church camp. But at church camp, he falls in love with the camp director’s beautiful daughter, Avery (Bailee Madison), and ultimately develops close friendships not just with Avery, but with his bunkmate George and George’s love interest, a quirky girl named Presley (Kat Conner Sterling). Along the way, there is a camp competition, in which Will faces his nemesis, Sean (Iain Tucker), who is a rival for Avery’s affections. One night toward the end of camp, there is an emotional musical scene (how can there not be?), in which tension builds around whether or not Will will open his life to God and turn his life around. Woven into this plot are energetic catchy musical numbers (music producer, Adam Watts) choreographed to rebooted popular Christian songs of the 1990s. The result has been contagious for a fandom who are now “legit obsessed.”

- A Week Away Is a World Away from Zoom School and Our Hypermediated Pandemic Lives

Filming wrapped at the end of the summer in 2019, and the young actors, according to their own accounts, truly were as carefree and joyful as they appear on screen. Filming was a blast, actors got to splash around in the lake, dance up a storm, joyride around set in golf carts, and socialize in the woods together at a picturesque YMCA camp in Tennessee. At the time, there was no hint of the pandemic disaster that would unfold less than six months later. When watching this film, we are essentially watching a time capsule of “innocents” just before our world came crashing down.

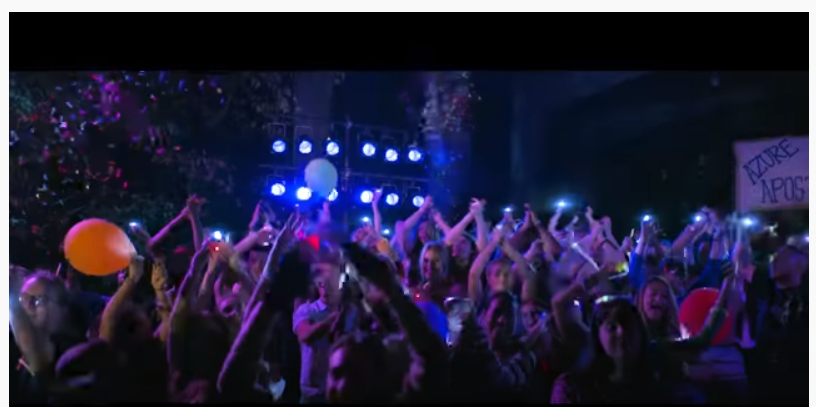

Viewers get to dance along to the infectious jukebox soundtrack, live with buddies in rustic cabins, swim with friends in the lake, attend camp concerts in shoulder-to-shoulder crowds, and even vicariously share a camp crush kiss, all sans masks and 6-feet social distancing health and safety regulations. Viewers’ comments express joy and relief and suggest experiencing this film as a veritable oasis in the dry hard months of the pandemic — one posting on the trailer observing that “it is almost as if Netflix knew 2020 was coming.”

The teens in A Week Away have no cell phones at camp and thus there is no texting back and forth. There are also no computers or WiFi. Communication is ubiquitously face-to-face and takes place in what my former Media Studies professor and theorist Anne Balsamo talks about as “pheromonal space.” That is, this is the kind of non-digital space where organisms are close enough to biochemically interact and communicate. In these “pheromonal” camp conditions, relationships blossom and friendships deepen. In effect, the film provides viewers a vicarious sanctuary from the kind of hypermediation and “pheromonal” isolation that has only accelerated in the pandemic.

But rather than being a weeklong media fast, the film presents the characters’ interactions with “old media” with great fondness and nostalgia. George both draws and reads vintage-stylized comic books as a way to express his love for Presley. In the year they have spent apart, he has written her 365 letters, not on email but by hand with actual pen and paper, though he cannot bring himself to give them to her. A little stalkerish, yes, but it is “old school” media kind of stalkerish, not going through all your exes’ photos on Instagram stalkerish. We see images of an old TV set and vintage VHS tapes in George and Will’s cabin. George watches and quotes from a VHS copy of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, while wearing a “Save Ferris” T-shirt. When Avery wants to share “a memory” with Will, she offers it to him in the form of a blurry retro Polaroid photo of the four friends together.

There is a manageability and more human-scale suggested about this slower, clunkier, less-sleek media that pairs well with the film’s nostalgic ‘90s soundtrack. There is palpable pleasure, ironically, to streaming this fantasy of sanctuary from hypermediation, even as hypermediation permits our immediate access to it.

Film viewers’ virtual sojourn at church camp, stripped of the anxiety and all-consuming, 24/7 nature of digital media and the noise of its incessant notifications (like the one I received from Netflix about this very film), creates space to breathe. And in this breathing space, the film suggests are opportunities for deeper connection – to friends, to community, to potential loves, to the natural world, and to God. In an epiphanic moment, Will realizes that away from the city at this camp, away from everything he has known, he has never felt so “connected” or felt such a sense of true belonging. In the YouTube comments responding to a clip from this scene, a poster who may be experiencing excess digital connection during the pandemic wryly remarks:

2. Kids Get to Play and Be Kids Again, and Teens Are ‘Legit’ Missing Camp

Water fights, dodgeball, cornhole toss, hula hoops, tug of war, talent shows, an epic paintball battle, and even a huge water trampoline “blob.” There is a ton of unadulterated kid play in this film, and it is all non-digital.

For kids who have been chained to Zoom screen school for the duration of the pandemic the film provides a portal to a world where teenagers are free to run and play together, unfettered by digital surveillance, parent surveillance, or CDC restrictions.

In the context of the pandemic, this is heady stuff, and not just for kids but for adults, too. The “Mom reviewer” at ParentPreviews.com declares, “Not even a predictable plot can dampen this movie’s infectious happiness.” Infectious indeed for the trooper of an aunt below who watched the film with her nieces six times, until it finally wore down her defenses and took hold.

In the comments on the trailer and movie clips postings, teens who had to stay home last summer clearly get a jolt of missing camp in watching the film. And church summer camps were quick to jump on posting stills or look-alike photos from the film to social media in order to advertise summer camp enrollment. The film features a scene in which Will, who is afraid of heights, faces his fears and takes a “leap of faith” onto an inflated blue and yellow lake “blob,” all the while singing Steven Curtis Chapman’s rousing 1999 hit “Dive.” (Look closely at the camp’s lifeguard, and you will see a cameo from Steven Curtis Chapman himself playing this role.) That this “leap of faith” image from the film is a great tool for marketing Christian camps has not been missed.

A Week Away’s creative choices vis-à-vis the presence or absence of media representations in the film tap into the fact that summer camps are often the few spaces where iGen teens get a break from the pressures of social media and digital hyperconnectivity. A national survey in 2019 found that 93% of teens who attended overnight summer camps that banned smartphones “felt relieved for the break from social media,” and 80% “felt less anxious and depressed because they didn’t have to keep up with social media.” Even as teens stream this film from spaces of hyperconnectivity, A Week Away lets viewers fantasize about a world away from social media’s perpetual (and exhausting) digital labor.

There is so much up-close-and-personal reverie in this film, joyfully unfettered by Covid viral considerations, that you can almost smell the sweaty camp teen spirit. No wonder viewers living under more than a year of restrictions and mortal fear of illness and death have embraced this movie. Its playful scenes feel transgressive, liberating, and cathartic, while offering hope that, at some point, such scenes will become possible once more.

I confess I tend to stereotype High School Musical and teen romance plots as the fare of adolescent girls, so I was touched by just how many comments posted by those with male-identified names spoke of their emotional connection to this movie, such as “Dave” who cried at its beauty, and “HercMan,” who found watching the film’s songs “Dive” and “Where I Belong” helped ease his anxiety and depression.

3. Christians in the Woods Are Having a Moment

Church camps are of course nothing new. And as environmental historian Michael B. Smith has demonstrated, summer camps dating back to the nineteenth century have always presented themselves as healthful sojourns to escape the stressors of urban industrial life. Church camps have historically combined an idyllic retreat into the wholesomeness of nature with openings for greater spiritual growth and fellowship. The formerly YMCA-associated, New York-based Camp Dudley (f. 1885), the oldest continuingly operating boys camp in the U.S., was one of the first camps to advertise explicitly its instillment of Christian values and development of campers’ spiritual life. A close relative of mine identifies his most transcendent moments at Camp Dudley as equally swimming in the lake and “Hymn Sing” on Sunday nights. Communing with nature and singing together with friends were the two things that truly spoke to him as a young man. For evangelicals, getting saved at “Bible camp” or “Jesus camp” is a rite of passage and time-honored tradition.

Since the pandemic, though, the popularity has skyrocketed of hiking, camping, walks in the woods, biking, and any outdoor activity in nature. Coronavirus bike shortages have driven up wait times for bike orders close to a year, and delayed kayak orders are in the same boat. At the same time, the Japanese phenomenon of Shinrin-Yoku, or “forest bathing”, already introduced to the U.S. several years ago, has taken off and become a Japanese cultural export around the globe. During the pandemic, “forest bathing” groups that take slow, mindful walks through the woods have popped up across MeetUp.com and at local arboretums and botanical gardens. A slew of news articles report the psychological benefits and the boost to the immune system of getting out in forests, especially as a prescription for coping with Covid pandemic stress.

Since the practice of Shinrin-Yoku is more Buddhist and Shinto-inflected, U.S. evangelicals have come up with their own version of forest bathing, called “Christian Forest Therapy” or “Bible-Based Forest Bathing.” During the lockdown, the Christian Forest Therapy group on Facebook posted a meme that encourages Christians to spend time in the forest as “GOD’s Original Prescription for Social Distancing.” In a series of posts, “God’s created forests” are portrayed as therapeutic places to heal by connecting to the presence of God.

More recent posts speak to the noise and distraction of our hypermediated world, encouraging Christians to take a break from the chaos, slow down, get quiet, and tune into God in the calm of the forest.

In one of the more moving scenes in A Week Away, Avery takes Will on a walk through the forest to a special prayer garden she has planted for her deceased mother. She tells him that she comes to this place in the woods in order to feel close to the spirit of her mother, whom she has faith she will one day see again and be reunited. As Will bonds with Avery over their mutual tragic loss, this scene definitely made me think of the many children and teens around the world watching this film who may have lost a parent, or even both parents to the pandemic, especially in hard-hit countries. Seeing Avery and Will both coping with parental loss might make these children feel seen and not so alone. Ultimately, the shared interlude in the woods, contemplating the nature of life and death, loss and the eternal, brings them closer together. They begin to fall in love, and a duet (“Place in This World”) ensues. It is also here, in the middle of the forest, that Will’s heart begins to open and heal. In essence, it is “Christian Forest Therapy” in action par excellence.

4. A Week Away Is the Anti-Cuties and Wins Back Netflix Deserters to Pure Flix

After Netflix’s widely publicized Cuties debacle, A Week Away’s wholesomeness is a breath of fresh air for many viewers. In the summer of 2020, Netflix cancellations spiked eightfold as disgusted viewers protested the hypersexualization of young girls on Netflix posters advertising a French-language film about a young Senegalese girl who joins a dance team and “explores her sexuality.” The poster displayed pre-pubescent girls striking overtly sexualized poses while wearing skimpy suggestive outfits. Streaming service Pure Flix, self-positioned as the evangelical alternative to Netflix, has profited from the disaffection of some audiences with Netflix, capitalizing on a growing (no longer so “niche”) market for faith-based, family-friendly media in the U.S. and Canada. Discerning this growth potential globally, SONY Pictures strategically acquired Pure Flix in November of 2020, attracted by the profitability of the faith-based media market and the loyalty of its streaming subscribers.

In contrast to Netflix’s Cuties marketing, youth bodies in A Week Away are concertedly not sexualized. All dance numbers are choreographed with energetic but tasteful moves, and there is not a single twerk to be found. In the rousing lake-splashing number, in which Kevin Quinn performs Steven Curtis Chapman’s song “Dive,” the cast is clad in stylish, youthful, but modest swimwear. The girls sport brightly-colored maillots and swim shorts, and even the boys’ chests are covered in T-shirts or tank tops. Kevin Quinn may very well have a killer six-pack but we never see it. If you think this is a mere quaint concession to evangelical sensibilities, think again. Modesty fashion is now a 283-billion-dollar market, and modest swimwear makes up a good chunk of that. Nike has introduced a line of modest swimwear targeted toward Muslim women, and countless modest swimwear online start-ups now cater to consumer demand, not just from Christians but other women and girls who, for a variety of reasons, wish to expose less skin.

Bodies in the film also come in all shapes and sizes, and all the girls are refreshingly healthy-looking instead of super skinny or anorexic-looking. Avery’s friend Presley is on the curvy side of the spectrum for Hollywood casting, and yet George remarks she “could have any guy she wanted.” Camp flirtations are sweet, romantic, and respect boundaries without being weirdly prudish. There is no “purity culture” police, no scolding chaperones, nor do ultra-conservative evangelical notions of supervised courtship make an appearance that might compromise the film’s wider audience appeal. To be sure, there is definitely no underage sex or make-out scenes. Real-life teen alumni from church youth camps may contend this absence requires the most concerted willful suspension of disbelief. Be that as it may, Will and Avery have meetings alone in the woods together, embrace as they dance along the edge of the lake to the setting sun, hold hands, and even kiss. What some viewers dub “cheese,” others find to be charming and delightful.

A Week Away’s wholesome content and aesthetics have, in turn, re-attracted defectors from Netflix, offering them a reason to return. This makes smart business sense and continuing on this trajectory could provide a path for Netflix to capture more of the faith-based market share.

5. It’s Faith-Based But Not “Too Jesus-y”

The opening credits for the film show an animated scene of items each main character is packing for camp. Conspicuously absent from these items are bibles – normally a staple on the packing list for church camp. Avery’s journal, which is set to be packed, does show a torn out page that reads, “For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you a hope and a future,” but the attribution to Jeremiah cannot quite be read and remains hidden.

Although at one point Will quips that he is stuck in the middle of nowhere surrounded by a bunch of “Jesus Freaks,” references to Jesus are few and far between. More general references to “God” predominate, but even these remain more subtle and less overpowering. A prime example is Will and Avery’s duet of the Michael W. Smith and Amy Grant co-written Christian-rock crossover hit “Place in this World,” which hit the #6 slot on the Billboard Hot 100 back in 1991. But the lyrics, which are about existential crisis, more ambiguously (as many contemporary Christian songs do) evoke God in the second person: “I need your light to help me find/My place in this world.” Leaving these references open to interpretation and code-switching enabled this song successfully to reach a much wider audience beyond simply evangelical Christians back in the ‘90s, and it performs similar work here. The more multivalent “you” is one of the many ways the film skillfully navigates the kind of offputting exclusionary, narrow, or judgemental associations many Millennials and GenZers have with “Jesus language” that Diana Butler Bass unpacks and counters in her recent book, Freeing Jesus.

Even the campfire “getting saved” moment in the film is not explicit to viewers unfamiliar with evangelical culture and practices such as “sharing testimony.” There are no declarations of accepting Jesus into their hearts or giving one’s life over to God. Jesus is never mentioned. And there is no explicit altar call. Instead the campers passionately sing a medley of two songs, Rich Mullins’s stirring “Our God Is an Awesome God” (1988) and for King & Country’s 2018 haunting hit, “God Only Knows.” It is an emotional scene in which teens rise one by one to join the singing. As they do, we watch in suspense as Will struggles to cope with his troubled past and his parents’ deaths, while trying to figure out what he might choose for his future. Will he rise and join the other singers? To the uninitiated viewer, though, this scene could be read as merely a powerful camp sing-along of bonded friends, reflecting on what they have learned from their camp experience. And this ambiguity extends to teens who come from families associated with non-evangelical “mainline” churches. As someone raised in a traditional east-coast Episcopal church, I had never heard of things like “altar calls,” “getting saved,” or “bible studies” until I moved to Southern California to become a doctoral student in my twenties. And nobody I knew from church spoke about Christ, God, or the Lord in what seemed to me at the time like oddly folksy terms like “Jesus.” So, though most certainly evangelical in its ethos and crafting, the film creates space for viewers (Catholic, “mainline” Protestant, and even beyond) to interact and interpret the story in different ways. At the very least, by comparison, the film is somewhat less overpowering and adopts a lighter touch than most of Pure Flix’s bludgeoning, triumphalist lineup of faith-based films.

6. It Stresses Inclusivity and Acceptance, #NotTrumpy Christianity

Since A Week Away’s debut, when the cast has been interviewed as to what the film is about, they reply a number of things (the power of love, kindness, forgiveness, second chances) but the strongest emphasis is always placed on the message of “acceptance.”

The setting might be woodsy Tennessee, but the vibe is concertedly un-Trumpy in the community emphasis on kindness, unconditional love, and acceptance. These highlighted themes reflect the growing trend of Millennial evangelicals diverging from their parents’ politics on a range of issues, from marriage equality to climate change, and from immigration policy to racial equity. Evangelical youth are increasingly disaffected from Christianity, but those who stay are also more likely to split with the Republican Party, and surveys suggest that Trump’s actions are to credit (or blame) for this defection.

The film’s music score also communicates a more loving and inclusive culture that speaks to Millennial and GenZ sensibilities. One of the key musical numbers in the film is a song called, “Good Enough.” This song, which is written by Adam Watts and performed by the four main leads, sends the message in the social media age that comparison is the thief of joy and that we are all “good enough” in the eyes of the Creator. As Presley and George both sing of their insecurities about sharing their feelings for each other, their friends reassure them that “God made you just as you should be – good enough – more than good enough.” Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way” it ain’t, and not surprisingly there are no explicitly gay characters in this evangelical teen film, but it does send the broader message that you are not a mistake and are made perfectly just the way you are. In an interview in teen fan magazine Tiger Beat, Jahbril Cook, the Black-Filipino actor from Alaska who plays George, advises fans, “Anyone who tries to change themselves for another person has failed miserably!”

The fact that Amy Grant, who went through a very pubic divorce and has a large gay fan base, makes a cameo in the film, in addition to inclusions of her music (“Baby, Baby”), also sets a tone of inclusivity. Grant was one of a group of prominent evangelicals who signed a letter protesting then President Donald Trump’s budget cuts, and she has done interviews with GLAAD media and PrideSource about the evolution of her views over time about sexuality and her support for LGBT people. More recently, there was speculation about whether her Valentine’s Day-themed “Say It With a Kiss” (2017) actually features a same-sex couple kissing. Grant has not gone as far as American Idol-winner and My Savior artist Carrie Underwood, who has publicly declared her support for marriage equality, but Grant resonates as the face of a kinder gentler compassionate evangelicalism. In fact, her cameo in the film shows her in a helping role, ministering first aid to a camper who has been injured.

In terms of diversity and inclusivity, the larger ensemble cast of singers and dancers is ethnically diverse and multiracial, which is on target, especially since about 1 out of 3 American evangelicals is a person of color. However, the roles of George and his mother Kristen make up just two of the seven principal roles, and here the production definitely falls short, particularly considering the increased public attention being drawn by scholars such as Anthea Butler and Randall Balmer to the historical entanglements of white evangelicalism and racism. In the A Week Away sequels to come, of which there will surely be many, I predict starring roles for Asian-American and Latinx actors. As it is, the supporting cast of color steal some of the scenes, and fans have speculated from the very brief glimpse we are shown of Will’s family photo that his deceased mother was Latina.

The film’s “sorting” scene of campers into teams for the “warrior games” competition is notable for its attempt to practice more cultural sensitivity awareness than one normally expects in a teen film about summer camp. At most camps, the internal camper competition is usually termed “Color Wars,” in which campers are divided up into teams (red, blue, green, etc.) associated with a particular color. Obviously, the term “Color War,” can have disturbing connotations, and the screenwriters (Alan Powell, Kali Bailey, Gabe Vasquez) recognize this, opting for alternative terminology. “Warrior games” has its own problematic connotations but perhaps less so than “Color Wars.” At many camps, these “wars” can take on a “tribal” performative cosplay aspect, in which campers compete against each other as “warring tribes” and face “war” paint is deployed for dramatic effect. However, in this film’s “sorting” tribunal, a combination of Harry Potter’s hat sorting ceremony and Reality TV Survivor aesthetics, the camp director dresses up as the Scottish historical figure of William Wallace from the Mel Gibson 1995 film, Braveheart. So yes, there is face paint, tribalism, and warrior spirit in this scene, but the script carefully makes clear that the cultural references here are to European culturally “Celtic” warriors and not to the appropriation of Native American cultures and ceremonial customs. George’s mother, Kristen, specifically emphasizes this point by teasing the camp director about his obsession with Braveheart, in such a pronounced way that it leaves little chance of misrecognizing the cultural reference in this scene. The homage to Braveheart comes as little surprise to media and religion scholars who know from Stewart Hoover and Curtis Coats’s ethnographic media research that Braveheart holds strong resonances for evangelical men who draw from that film positive models of masculine protection, power, and purpose.

There is much more to say about A Week Away, its production choices, and its public reception, but unlike Netflix’s trailer, I hesitate to give it all away. Suffice it to say, though, that both Netflix and SONY Pictures astutely recognize the profitability of faith-based market expansion and the bonus of crossover titles, such as this one, for broader global market appeal. What’s more, in the phenomenon and teenage rite of passage that is U.S. summer camp, there lies infinite narrative, aesthetic, and entertainment territory to be mined. That some Hollywood producer has not already cleverly snapped up and executed a Netflix version of Roger Bennett and Jules Shell’s Camp Camp: Where Fantasy Island Meets Lord of the Flies (2008), a hilarious treasure trove of artifacts and nostalgia from Jewish summer camps from the 1970s to the 1990s, is most certainly a lacuna in the camp film genre.

Whether forest bathing, camping, or simply dreaming of summer camp, Covid-weary audiences are seeking antidotes for pandemic cabin fever. Media production companies and platforms that respond to this moment by serving up stories of greater connection to the natural world, to other humans, to experiences of community, to larger existential questions, and to nostalgia for a pre-pandemic less digitally mediated world, will find this a smart investment. This is so even as the immediacy and dynamics of hypermediation become not only the vehicle to access these streamed fantasy images of de-escalated mediation but make possible the very platforms on which fans across the globe easily connect with one another to share their love of these stories. More unclear is whether or not, when we “return” from immersive virtual sojourns like A Week Away, we will be energized and inspired to cultivate and repair our own human connections within the “pheromonal space” of a promised post-pandemic world.

Sarah McFarland Taylor is a professor of religion, media, culture, and environment at Northwestern University. She is the author of Green Sisters: A Spiritual Ecology and Ecopiety: The Dilemma of Environmental Virtue. She is currently working on May the Forest Be With You, a book that examines representations of trees as spiritual media that includes explorations of Shinrin-Yoku and Christian Forest Bathing movements in the U.S. marketplace.